Washington, DC set a record last week: The hottest summer in 140 years. Eleven consecutive days with highs over 95. Five days with the average high of 99.5. (The highest temperature reached 105, one degree short of the 1930 high.) An historic heat wave.

But our house has air conditioning. And it was working. My daughter told me that when she was little and we didn’t have air conditioning I made her go to sleep in a wet T-shirt. (I don’t remember that.) Of course, we had never experienced a heat wave quite like this one.

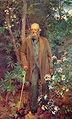

So I spent a lot of last week thinking about 19th century life without air conditioning when parks and green spaces offered the city’s only respite from the heat. I had written “A Place to Ponder and to Rest,” a piece on Frederick Law Olmsted and the U.S. Capitol Grounds for Cobblestone, the children’s American history magazine. Olmsted envisioned a space where members of Congress could temporarily escape the demands of their work (or the tempers of their colleagues). He designed a space that was elegant and graceful and naturalistic. To create a relaxing atmosphere he added a summerhouse with bluestone benches, wrought iron, Spanish mission tile, and a fountain. The Grounds became a place where people could escape from the heat on hot summer days.

This landscape architect succeeded in part because, as the editor of the Olmsted Papers Charles Beveridge told me, Olmsted was intense, enthusiastic, and energetic.

Cobblestone’s July/August issue is entirely devoted to Olmsted and includes articles by Gina Hagler, Helen Kitrosser, Marcia Amidon Lusted, and Barbara Brooks Simons. Gina Hagler calls Olmsted a visionary. “He was one of the first people to understand and articulate the fact that time spent in observation of nature’s beauty is vital to human health and happiness.”

I read the magazine from cover to cover and found many interesting facts about Olmsted:

• As a young man Olmsted worked as an apprentice to a surveyor. He later sailed to China on a yearlong voyage (along the way suffering from typhoid fever and scurvy). He then purchased a farm on Staten Island and became a full-time farmer.

• In 1850 Olmsted, at the age of 28, began a walking tour of England. He fell in love with the idea of a public park and wrote “The poorest British peasant is as free to enjoy it . . . as [is] the British Queen.” Olmsted could have added “probably more so.”

• In competing for the commission to design Central Park Olmsted aimed for “a planned park with an unplanned feel.” The construction of the park was a huge undertaking involving 20,000 workers who planted 270,000 trees and shrubs.

• Overseeing the design and construction of Central Park was so taxing that as soon as he finished he went to Europe for a six-week rest cure.

• Frederick Olmsted’s brother died in 1857 leaving behind his wife Mary and their three children. Two years later Fredrick married Mary and together they had four more children.

• In designing the grounds for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition (Chicago’s world’s fair) Olmsted inspired his successors to plan equally grand public parks and gardens. Barbara Brooks Simons quotes the architect Daniel Burnham who paid tribute to Olmsted in a toast at a dinner just before the fair opened: “An artist, he paints with lakes and wooded slopes; with lawns and banks and forest-covered hills; with mountainsides and ocean views.”