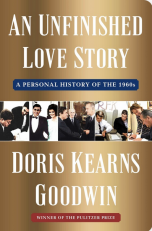

Multiple journeys make up the crux of An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s. Memories of our own lives and that of our nation quickly resurface, eliciting different emotions—ranging from empathy to outrage—and occasionally instilling pride and love of country or nostalgia for days gone by. Historian and biographer Doris Kearns Goodwin invites us to take part in a long, eventful, and bumpy ride as she chronicles her husband Dick’s education, the twists and turns of his career as presidential adviser and speechwriter, his aging, and the illness that ends his life. “What makes life worth living?”—a question she attempts to answer.

One of these journeys is deeply personal. The Goodwins embark on a thorough examination of their own past and search for identity, experiencing waves of bittersweet nostalgia. When Doris tells her husband she is “totally smitten” with him after rereading a letter he wrote at the age of twenty-three, he answers, “I rather envy him myself,” and then goes on to explain, “It’s not simply that I’m much, much older now. He’s got something I’ve lost along the way.” There is a sense of mourning, stronger and more overpowering than nostalgia.

The couple did not always agree as to the motivations and personalities of the Kennedys and the Johnsons. Both developed intense, intimate relationships with presidents and their families. Doris and Dick were often subject to the presidents’ whims, eccentricities, and shocking stubbornness. This did not mean they always saw eye to eye. Coming to grips with that was part of their own personal journey. Doris tells us that at the age of eighty-five, Dick’s festering bitterness towards Johnson softened.

Another journey leads husband and wife to reflect on the roles they themselves played to change the course of history. Doris talks about Dick’s “love affair with America” and his belief in Abraham Lincoln’s credo, “the right of any man to rise to the level of his industry and talents,” his efforts to end the war in Vietnam, and his devotion to civil rights, the Alliance of Progress, and the Great Society. She speaks of the sixties as “a time when a candidate’s word represented a commitment to a prescribed course of action. What one said mattered.” It was a time when “we still had a conviction that sweeping change was possible.” And a time when young people held sway.

Doris expands on how their own lives were interwoven with history and politics. She discusses Dick’s speechwriting—his love of words and the depth of his convictions—and we hear his favorite lines, “If the President does not himself wage the struggle for equal rights—if he stands above the battle—then the battle will be inevitably lost.”

To take the time as the Goodwins did to reflect on the past and sort through the hundreds of boxes of memorabilia that Dick had saved was both a demanding task and an extraordinary opportunity, one often filled with love, tenderness, and laughter despite poignant moments and a few regrets. “So long as we were working together, so long as we were opening boxes—learning, laughing, discussing the contents—we were alive. If a talisman is an object thought to have magical powers and to bring luck, this book was our talisman.”

After Dick died, Doris left the farmhouse in Concord that had been their home for twenty years. Once settled in a condo in Boston, she gathered all the notes from those years spent digging and reminiscing and she began writing. She started her memoir with the day she and Dick first met. Life had come full circle.

Time spent sorting and the reflecting can prove a great gift. Decluttering—in limited spurts—appeals and I’ve been somewhat successful this year—camping gear we will no longer use, tools for home renovation projects we have no plans to undertake, picture frames (but not the photos) of ancestors, known and unknown, board games with missing pieces (the ones we thought might turn up under the couch but have not resurfaced in decades), and other odds and ends we’ve accumulated given we’ve lived in one house for forty-three years. I have yet to sort through boxes of papers and filing cabinet drawers—not as many as Dick accumulated, but still a fair number.

I’m not ready. It’s too soon for all that. But I am grateful for all that those boxes contain—the papers, the letters, research notes, manuscript drafts, newspaper clippings, and the Oracles essays.

When I do begin, I will look back on my own journey and think of the Goodwins. An Unfinished Love Story captures the words in Tennyson’s Ulysses: “I am a part of all that I have met… Tho’ much is taken, much abides.”

And Ithaca will be top of mind—remembering these lines in C. P. Cavafy’s poem:

Always keep Ithaca in your mind.

To arrive there is your ultimate goal.

But do not hurry the voyage at all.

It is better to let it last for many years;

and to anchor at the island when you are old,

rich with all you have gained on the way,

not expecting that Ithaca will offer you riches.